From Mali to Iraq, people in conflict zones are proving especially vulnerable to climate extremes

An estimated 100,000 people died and livestock were decimated when a long drought hit West Africa in the 1970s.

Isa, a 61-year-old community leader from northern Mali, recalled: “At that time, we only had to search for food. We could move freely with our animals. Now, we can’t even search for food. We are forced to stay in place or move to cities because of the insecurity.”

Desertification has been accelerating in Mali for decades; rains are rare and increasingly unpredictable. Faced with such challenges, herders would normally travel further afield with their animals to find water and land for grazing.

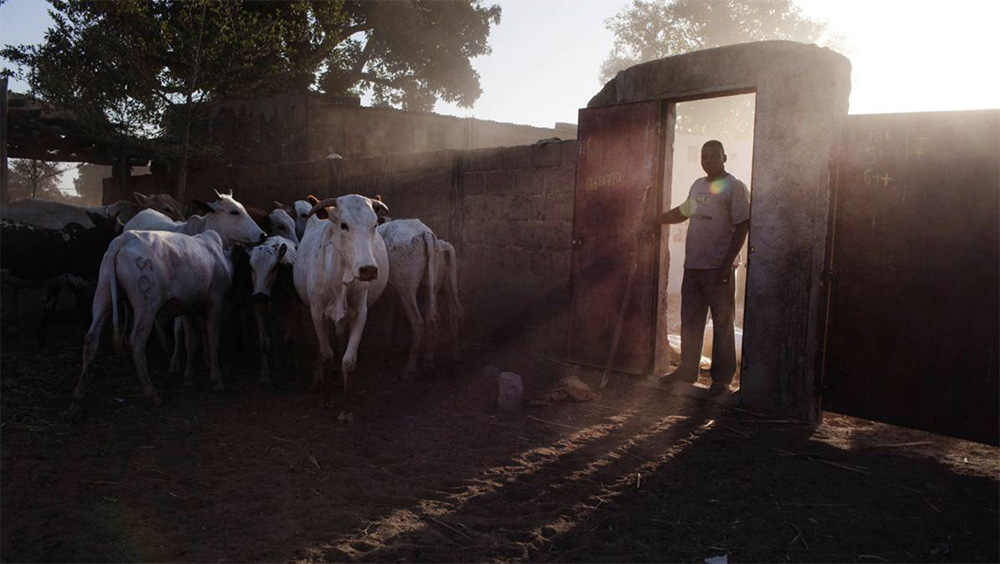

But years of conflict and insecurity in northern Mali have deterred herders from travelling for fear of being attacked. Instead, they stay in one place, often close to water sources. This in-turn causes tensions with farmers and fishermen.

Unable to draw on state support due to the conflict, the herders can only watch as their cattle – their only assets – become weaker. They are forced to sell them at steeply discounted prices to gain any kind of income. An already poor population becomes poorer.

This is perhaps the most striking example we came across when researching how conflict harms people’s ability to adapt to climate change. It is by no means a solitary example.

Our new report has shown that people living in conflict zones are disproportionately affected by climate change. Of the 20 countries deemed most vulnerable to climate change, 12 are mired in conflict.

People living in conflict-zones already face extreme stress and hardship. Climate variability and shocks further worsen their predicament. Assets that should help them cope with change, such as state institutions, essential services, social cohesion, livelihoods or even freedom of movement, are profoundly disrupted by conflict.

CASUALTY OF WAR

Environmental harm stemming from conflict can further limit people’s ability to adapt to climate change. Too often, the natural environment is directly attacked or damaged by warfare. Attacks can lead to water, soil and land contamination, or release pollutants into the air. Explosive remnants of war can contaminate soil and water sources, and harm wildlife.

In Fao, south of Basra, Iraq, people blame their water and farming problems on the felling of date palms for military purposes during the Iran-Iraq war. They have not grown back. This environmental damage has been compounded by rising temperatures, droughts, desertification and soil salinization.

Today, there is a marked increase in sand and dust storms in Iraq – from fewer than 25 days of local dust storms a year between 1951-1990, to some 300 in 2013. This has contributed to transforming fertile soil into desert areas. “Before, rain was falling. Now, dust is falling,” mused one of our colleagues.

Climate change is cruel. While it will be felt everywhere, these examples from Iraq and Mali illustrate how its most crippling effects will be borne by the world’s most vulnerable. Violence and instability rob communities and institutions of the chance to adapt.

STRONGER CLIMATE ACTION

The International Federation of Red Cross Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) has assessed that by 2050, 200 million people could need international humanitarian aid every year, double the number in need now. Humanitarian organizations are already struggling to respond and will not be able to meet exponentially growing needs resulting from unmitigated climate change.

Major efforts – in the form of significant systemic and structural changes, political will, good governance, investment, technical knowledge, a shift in mindsets – are needed to ensure that communities hit hardest get the support they need to cope and adapt.

Despite people living in conflict zones being among the most vulnerable to the climate crisis, they are also the most neglected by climate action. We urgently need to work together across the humanitarian sector and beyond to reverse this trend and ensure that populations enduring conflict are not left behind by climate action. We need to skill-up and strengthen anticipatory responses – reducing risks and exposure go a long way to protecting people.

A greater share of climate finance also needs to be allocated to climate adaptation. There is a gap in funding for climate action between stable and fragile countries. At present, the bulk of climate finance is used to support efforts to reduce carbon emissions, which is essential. But such efforts must be complemented by activities to help communities adapt to a changing climate.

Catherine-Lune Grayson is a policy adviser at the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and author of a new report on climate change and conflict. This blog was originally published by the Thomson Reuters Foundation.