Soumya Chattopadhyay takes a look at Prindex’s 2017 trial data from India, and raises questions to drive future research.

In October, Prindex will publish our first full tranche of data from 15 countries worldwide, and a total of 33 by the year’s end. While preparing our final survey, we conducted two trial runs, including one in India, Colombia and Tanzania in 2017. That data provides an insight into some of the questions that our full survey data – eventually to cover around 140 countries – may help answer.

Prindex’s 2017 field-test in India gathered results from 17,000 individuals in 20 states and three Union Territories (out of a total 29 states and seven Union Territories) in a nationally representative sample.

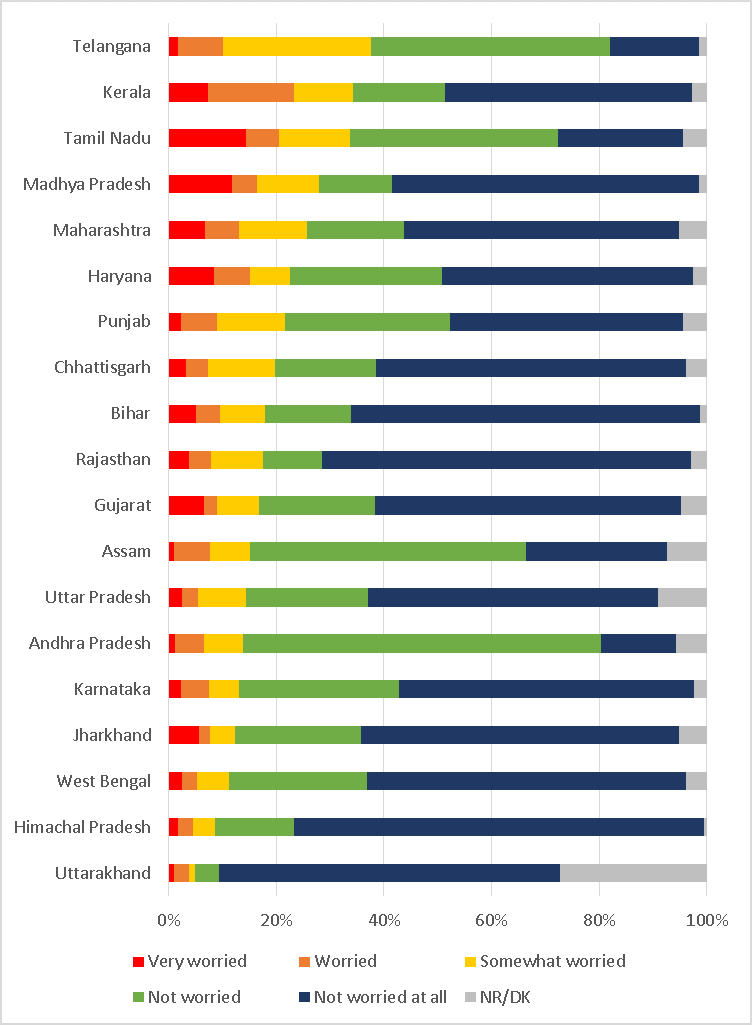

Our central survey question was: “How worried are you that you could lose the right to use this [dwelling] property or part of this property against your will in the next five years?” Respondents could rank their degree of worry across five possibilities, ranging from “very worried” to “not worried at all”.[1]

Interstate variations in perception of insecurity

There is remarkable variation across Indian states in the proportion of respondents who feel some degree of worry of losing rights their home: it ranges from over 37 percent in Telangana to less than 5 percent in Uttarakhand. However, the overall level of worry is not necessarily related to the intensity of worry in each state: Jharkand, where around 12 percent of respondents were somewhat-to-very worried about losing their property, had a higher proportion of people who were very worried than Telangana. Nearly 47 percent of the total worried) in Jharkhand were “very worried, versus only 5 percent of all respondents in Telangana feeling insecure.

Figure 1: The remarkable variation in perception of insecurity between states

Proportion of respondents in the state indicating different degrees of worry of eviction from current dwelling in the next 5 years; states are sorted on the vertical axis in decreasing order of perceived “insecurity”.

Note: For comparability between states, this chart excludes the state of Goa and the Union Territories of Chandigarh, Delhi NCR and Puducherry that have little or no rural land.

Some obvious causes of interstate variations

An initial glance at the differences between states highlights two potential drivers: variations in legal and policy frameworks; and different levels and concentrations of economic activity and population. A deeper analysis of the range of potential factors affecting tenure security across states requires additional data and research.

Legal and policy frameworks: in India, individual states are vested with the power to legislate and administer land-related property rights – particularly those pertaining to ownership and taxation. This has resulted in significant interstate differences in the legal and policy framework on land rights. Combined with variations in how they are administered and enforced, this can create different levels of how secure people feel about being able to hold onto their land and property.

Demographics and economics: another hypothesis is that in states with higher concentrations of economic activities and population, the greater pressure on land in turn drives up levels of insecurity and worry.

The rural-urban divide in perceived tenure security

PRIndex’s data revealed that rates of perceived insecurity about an individual’s dwelling are higher in urban areas compared to rural areas across 18 of the 19 states presented below. With the exception of Tamil Nadu, where rates of worry of eviction in rural areas exceeded that in urban areas by 14 percentage points, urban respondents felt more insecure than their rural counterparts, albeit with wide variations of difference:

- Rates of urban insecurity range from 39 percent in Telangana to 12 percent in Himachal Pradesh; and

- Differences between rates of perceived tenure insecurity in urban and rural vary from being less than 1 percentage point in Andhra Pradesh, to being 13 times more likely in urban than in rural areas in Uttarakhand.

Figure 2: Dwelling insecurity is more prvalent in urban locations

Proportion of respondents in the state indicating different degrees of worry of eviction from current dwelling in the next 5 years; states are sorted in decreasing order of perceived urban “insecurity”.

Note: For comparability between states, this chart excludes the state of Goa and the Union Territories of Chandigarh, Delhi NCR and Puducherry that have little rural land.

Possible causes of rural-urban differences in perceived tenure security

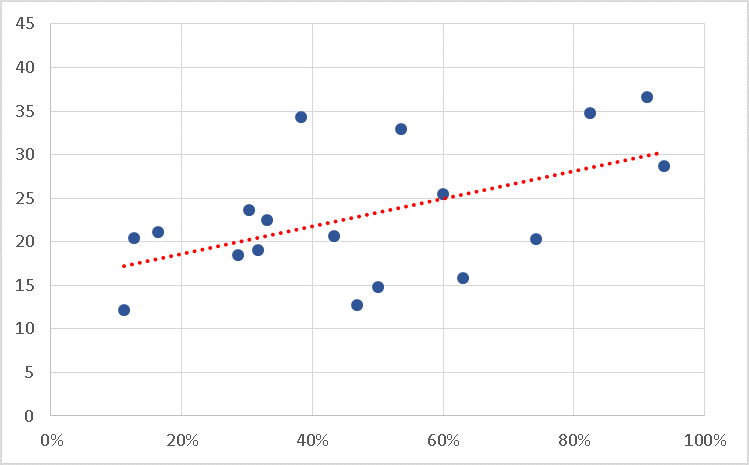

Beyond the disparities in state-level land tenure policy design and implementation, a probable explanation for greater urban insecurity is higher pressure of urban population density – both in terms of people per unit area, as well as urban population as a proportion of the total state population. Figure 3 plots rates of tenure insecurity in urban areas against urban population as proportion of state population, and demonstrates a positive relationship between the two: states with a higher proportion of urban population report higher urban dwelling insecurity, a correlation of 0.53.[2]

Figure 3: Higher urban density might drive dwelling insecurity

Proportion of urban respondents feeling some sort of worry of eviction from current dwelling in the next 5 years on the vertical axis; urban population as proportion of state population on the horizontal axis.

Note: For comparability between states, this chart excludes the state of Goa and the Union Territories of Chandigarh, Delhi NCR and Puducherry that have little rural land.

Other data sources: India Census 2011 in Office of Registrar General of India, Ministry of Home Affairs and Central Statistics Office, Government of India.

Other future analysis could explore complementary hypotheses to explain these interstate differences, such as differences in population density as well as the state-level economic growth rates.

Using new Prindex data to inform future research agendas

An initial look at the Prindex data in India has enabled us to flag potential links between tenure insecurity and different variables, such as legal and policy frameworks, different levels of economic development and demographics. Some of the results identify areas of concern, particularly the higher rates of tenure insecurity in urban areas compared to rural areas, when many states are experiencing rapid urbanisation.

There remains a rich seam of analysis to be explored in the Prindex data on India, and the data on 33 countries that will be published in early 2019. For example, our analysis here is not a reflection of insecurity about non-dwelling agricultural land that is expected to be of greater importance in rural communities. Land tenure security among farmers is a significant and important area of research– feeding into existing literature on its significance as a pathway out of poverty for poorer segments of the population that are often engaged in agriculture.

By complementing data on perception of security of dwelling with that of other land holdings (agricultural farm or other economic land) as well as more detailed socio-economic indicators of the households, we expect the Prindex database to offer a rich and deep understanding of the levels and drivers of perception of land security that has not been feasible so far. Assessments based on Prindex can form an important part of the toolkit for policy designers and administrators as they take on the complex challenge of reducing and eventually eradicating poverty from their countries.

Soumya Chattopadhyay is a Prindex researcher at the Overseas Development Institute in London

[1] We define “insecure” as being either “very worried”, “worried”, or “somewhat worried”. In the final questionnaire for 2018-19, we removed the unqualified “worried” category to simplify the options and make them more distinct.

[2] Overall proportion of urban population in a state is a proxy for urban population density; state-wise data on total urban and rural area is not publicly available.