Sexual extortion is a pervasive but often hidden form of corruption. Instead of money as a bribe, sexual favors are extorted in exchange for the provision of services or goods. This degrading abuse of power also touches the land sector, but remains largely hidden and unaddressed. Power dynamics and traditional gender roles make women particularly vulnerable to this specific type of corruption. Apart from causing great individual harm, 'sextortion' impacts society as a whole: it undermines gender equity, democracy, trust in public institutions, economic development,peace and stability.

At the crossroads of land, corruption and gender

Corruption impacts almost every sector worldwide. It can be found whenever officials entrusted with power lack integrity and abuse those who depend on their power. According to Transparency International (TI), in 2013 one in five people around the world reported that they had paid a bribe for land services. But while awareness of land corruption as a global phenomenon has increased, few studies focus on the inter-linkages between land corruption and gender and even less is known about the way corruption affects women differently from men.

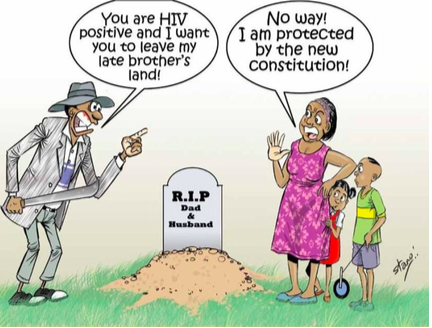

Land corruption often occurs where and when land governance and women's rights are weak. Women living in less developed countries are among the most vulnerable, particularly those who are widowed or single with children. In large parts of the world women only have access to land via their father, brother or husband. In countries where a man pays a dowry for his wife, a woman becomes part of the family of her husband and, as a consequence, may no longer be protected by the men from her birth family. The strong dependency on land, often coupled with care tasks in the household and limited representation in decision-making structures, make women prone to corruptive practices by land officials. Also, women often lack the financial means to register property or to lease or buy land in their own name and are excluded from powerful groups that influence policy. Other factors, such as lack of information, lack of literacy or simply time to go and stand in queues add to the vulnerability of women. Research from TI shows that, as a result, land corruption affects women differently and often more harshly than men. Such corruption may vary from payment of bribes to community leaders and land officials to obtain access to land or to obtain a land deed, to multinational investors appropriating land traditionally worked by women. Furthermore, increased pressures on land, due to factors such as climate change, population growth or large-scale land investments, often lead to increased violence against women. In the context of land scarcity, the need to secure land for the family becomes imperative, in some cases turning traditional practices -meant to protect widows- into forced marriages of widows with their husband's brother. Similarly, lack of access to land for young people may lead to land discrimination and expropriation of land held by elderly people, in particular women. In different parts of Africa, organizations such as Landesa and HelpAge have reported cases of widows being accused of witchcraft and, consequently, killed over land disputes. In Ghana, InsightShare in partnership with local partners Ghana Integrity Initiative, Widows & Orphans Movement and TI, facilitated the participatory video project 'Widow's Cry' giving widows a voice to speak out and demand action from those who abuse their land rights and to push for change in traditional practices preventing women from inheriting land.

As part of their recent resource guide for policy-makers, TI published a case study from Ghana showing the gender differences in how corruption is perceived and felt by victims and indicating that men and women often pay bribes for different reasons. For example, while men paid bribes to speed up land transactions to secure land for the future, women were more likely to pay bribes to prevent eviction. For women, the bribe was tied to an immediate threat, rather than a long-term need.

Participatory video project 'Widows Cry' in Ghana (photo: InsightShare / Transparency International 2017)

Mainstreaming sextortion in anti-corruption laws

Through its worldwide contacts, in 2008 the International Association of Women Judges (IAWJ) became aware of a gendered form of corruption that, despite its pervasive nature, had been largely overlooked in both corruption and gender debates. As the abuse occurs at the intersection of corruption and gender-based violence, the IAWJ termed it 'sextortion', realizing that naming the phenomenon helps to capture it and facilitates debate. What distinguishes sextortion from other types of sexually abusive conduct is that it has both a sexual and a corruption component. Nancy Hendry - senior advisor for IAWJ - thinks that this combination might be the reason why it often falls through the cracks and eludes prosecution as either sexual abuse or corruption. Hendry: "If you think of bribery as money changing hands, you may not see the exchange of sexual favors as corrupt. Efforts to combat gender-based violence often focus on sexual abuse that involves greater physical violence and is seen as less consensual than the kind of corrupt transaction that characterizes sextortion. Those who combat corruption tend to think in financial terms, so are often blind to wrongdoing that involves sexual favors.”

Another challenge is that in traditional anti-corruption discourse explicit references to human rights, including women's rights, are rare. However, research from IAWJ suggests that a gender approach to tackling corruption is highly relevant. Hendry: "There is growing recognition of the ways in which gender inequality and corruption are mutually reinforcing and of the pervasive and disproportionate impact corruption has on women’s lives – thwarting women’s opportunities to participate fully in almost every aspect of life, from education to employment, the political process, access to healthcare, land, credit, and government services". Although sextortion is a widespread problem, it is less likely to be prosecuted or reported than other forms of corruption. Apart from legal obstacles, such as misinformation and weak legal and institutional frameworks, cultural barriers and the fear of stigmatization and retaliation play a part in this under-reporting. The systematic collection of data and the sharing of good practices to inform legislators, judges and lawyers are important tools to make sextortion more visible. Also, awareness-raising of the broader public, the inclusion of sextortion in ethical codes, as well as safe reporting mechanisms and whistleblower protection for those who report sextortion, are critical to overcome barriers. Above all, it is important to mainstream sextortion in anti-corruption laws with the aim to penalize sextortion to the same extent as similar acts of corruption involving financial favors. However, whereas inclusion of sextortion in the legal framework is paramount, it is no guarantee for tackling the problem. Although sexual favors are specifically mentioned in the Tanzanian Preventing and Combating Corruption Act (2007), corruption, including sextortion, is still rampant.

Burden of proof

While regular definitions of gender-based violence usually always imply physical violence, in the case of sextortion psychological coercion is more often used, not necessarily physical abuse. Yet, the psychological harm of sextortion is likely to impact both the physical and mental well-being of the victim. For victims of gender-based violence, giving evidence is a difficult matter in view of re-experiencing of the abuse and because witnesses are often absent. As for sextortion, an additional difficulty is the question of how to avoid a case in which a person in a position of power offers to trade that power for a sexual favor being dismissed as 'consensual' and therefore non-violent? Given the fact that the burden of proof seems to be a significant obstacle for victims to come forward, even if the legal framework is in place, some experts suggest to apply a reverse onus for sex crimes. Shifting the burden of proof to the alleged perpetrator of sex crimes - presumed guilty until proven innocent - could be a useful means to correct a situation that would otherwise result in inequality. Other countries, such as South Africa, are pioneering with the (re)establishment of special courts for sexual offences cases. These victim-centered courts aim to have a prompt, sensitive and effective court system to improve conviction rates.

Inclusive land governance

In a context of high prevalence of HIV/AIDS infection, sextortion may even lead to death. Elizabeth Daley - team leader of Mokoro's Women's Land Tenure Security (WOLTS) project - first came across examples of sextortion during field research in Tanzania over 20 years ago. Daley: "At that time, this form of corruption, sexual extortion, did not really have a name". More recently, while identifying the main threats to tenure security for women in the WOLTS project’s research communities in Mongolia and Tanzania, Daley and her team found examples of sextortion occurring as access to communal pastoral land decreased due to expanding mining activities.

For example, in Tanzania, although the formal law grants women and men equal access to land, Daley explains that: "Communal land is under the administration of traditional leaders who are usually men. The strong influence of customary practices, according to which women and their land are often considered to be the property of men, was framed by one villager as ‘how can a property own property?’ These sorts of norms create a power dynamic whereby women who do not have access to money are therefore forced to bribe using sex as a currency. Even if women are aware of their statutory rights, which is often not the case, women find it difficult to challenge social norms and to come forward about sextortion because of the shame and fear of stigmatization.” Another barrier preventing women from denouncing this kind of abuse is the overall acceptance of gender-based violence and corruption as part of society. According to Daley: "One man we spoke with - a respected figure in the community - even told us that sexual relationships were necessary if a woman wanted to get access to land".

Women Rights Land and Property Project, Kenya Land Alliance (image: KLA 2014)

However, as Daley states: "Social norms can be influenced to become more inclusive". To this end, the WOLTS project has been testing approaches to building safe spaces where women and men, young and old, villagers and traditional leaders can meet and discuss the management of land and natural resources. The WOLTS team has been using tools such as role plays with men and women to raise awareness and build consensus on key land and gender issues in an effort to mitigate against corruptive practices such as sextortion in access to land.

As lead drafter of FAO's technical guide 'Governing Land for Women and Men', Daley drew her original inspiration for the WOLTS project to a large extent from the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests (VGGTs). Apart from key principles such as 'Consultation and Participation', 'Gender Equality' and 'Rule of Law', Accountability and Transparency are mentioned as guiding principles of implementation ‘to prevent opportunities for corruption’. Although not binding, the VGGTs provide a widely endorsed international framework and encourage states to set up multi-stakeholder platforms to facilitate good land governance at national level. This builds on national laws and on existing international instruments such as the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). CEDAW is legally binding in Tanzania since its ratification by the government in 1986. According to CEDAW, states are not just responsible for their own actions, but also for eliminating discrimination against women that is being perpetrated by private individuals and organizations. However, the challenge remains to translate this all down to relevant actions at the grassroots community level.

Holistic approach

Land now features within many of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including ending Poverty (SDG 1) and Hunger (SDG 2), achieving Gender Equality (SDG 5), providing Decent Work (SDG 8) and reducing Inequality (SDG 10). Similarly, combating corruption and bribery (part of SDG 16 - Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions) and gender inequality play an important role in many of the SDG targets. Whereas explicit attention to these issues is important, corruption and gender must also be specifically considered in relation to land. If the land-related goals are to be met, specific measures are needed to prevent policies to fulfill the SDGs from being weakened by corruption or inequality. Likewise, the SDGs and women’s land rights can only be fully achieved if corruption is tackled, stressing the need for a holistic approach with reference to all three closely-linked elements – land, corruption and gender. TI states that policy recommendations for achieving the SDGs on gender equality, land and corruption should include the prevention of corruption over land, the fulfillment of women's land rights and the promotion of good governance and equality in land administration.

Land corruption remains largely under-reported by journalists in the mainstream media and consequently, is often poorly understood by their audiences. TI's manual for journalists intends to support journalists in Africa who are investigating and reporting stories of land corruption. Further (field) research and disaggregated data collection on the links between land, gender and corruption are vital to making the root causes and impacts on societies of this shameful phenomenon of sextortion fully visible. This also helps to raise public awareness and to put pressure on policy-makers and land administrators to publicly acknowledge and tackle the problem and to monitor progress. Finally, naming and shaming and - literally - spreading the word 'Sextortion' is an important catalyst to finding ways to discuss this taboo issue and put it on the international political agenda.

Media help echo the voices of women climbing the Kilimanjaro in the name of women's land rights accross Africa (source: International Land Coalition 2016)

Sources used and suggestions for further reading:

- Women, Land and Corruption, Resources for Practitioners and Policy-Makers (Transparency International, March 2018): https://www.transparency.org/en/publications/women_land_and_corruption_resources_for_practitioners_and_policy_makers

- Gendered Land Corruption and the Sustainable Development Goals (Transparency International, September 2018): https://www.transparency.org/en/publications/gendered_land_corruption_and_the_sustainable_development_goals

- When the bribe isn't money: Gender, Corruption and Sextortion (lecture by Nancy Hendry - visiting Scarff professor, May 2018): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bx7JkQJJgxk

- Gender, Land and Mining in Pastoralist Tanzania (WOLTS Research Report No. 2, June 2018): http://mokoro.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/Gender_Land_and_Mining_in_Pastoralist_Tanzania_WOLTS_Research_Report_No.2_June_2018.pdf

- Combating Sexortion: A comparative study of laws to prosecute corruption involving sexual exploitation (Thomspon Reuters Foundation, International Association of Women Judges, Marval, O'Farrell and Mairal, April 2015) http://www.trust.org/contentAsset/raw-data/588013e6-2f99-4d54-8dd8-9a65ae2e0802/file