No! In Their Own Words: What indigenous people against the River Club development have to say

The controversial River Club site in Cape Town, where giant international retailer Amazon plans to build a South African headquarters, has been embroiled in a protracted legal battle – with rival indigenous groups campaigning for and against the development. Here are the voices of indigenous communities against the development.

When people speak about indigenous people worldwide, there is a tendency to speak about us as if we are something of the past. Lifeless, thoughtless and silent people who have no agency to articulate ourselves. The reality is: we are still here, we still exist and we have our methods of engagement. If only people would take the time to listen and consider us, to invite us in from the margins, after all, who better to tell our stories than us?

Here, Indigenous leaders against the River Club development offer insights into their thoughts and feelings on issues of land, environment and a history of oppression.

One, Chief Autshumao Mackie of the Western Cape Khoi/San Legislative Council, says when people talk about history and ask why this particular site is so important they tend to go back to 1652. But, Chief Autshumao says, “That doesn’t make sense to the true historical origin of what’s happening here.” Chief Autshumao says we have to understand the pre-colonial period.

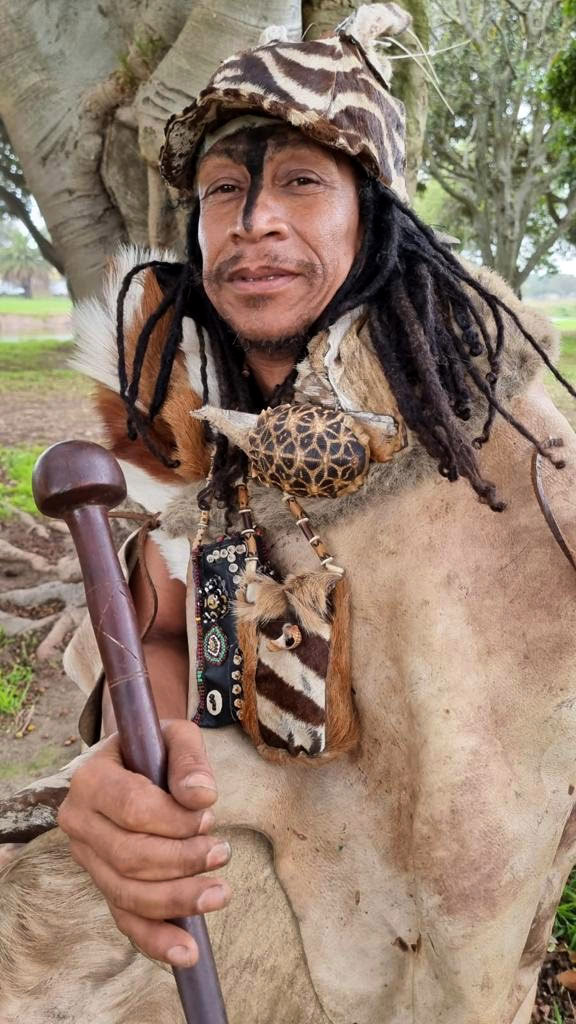

B’ia Bradley Van Sitters from !Khora||gau||aes Cultural Council shares the original name of Cape Town: ||Hui !Gaeb. It is a name long forgotten due to colonisation and trauma, he says. B’ia Bradley beams with pride as he explains that ||Hui !Gaeb means “the place where the clouds gather”.

On a mission to Namibia to connect pieces of history and memory, B’ia Bradley met indigenous people there who knew of ||Hui !Gaeb and an interconnected history and culture. They gave B’ia Bradley sacred sand from graves of leaders who had died and urged him to place it at a site of significance. He brought the sand back to the site at the Liesbeek River.

He says deep memory and layers of history make it a site of connection for indigenous people of southern Africa. It makes sense to B’ia Bradley that he should place the sand in a place of resistance, significance and importance.

Chief Sandra, a member of the Free Aboriginals, shared that the “Two Rivers” are important to her because, “This is where my kid brother and I would play, we had fun there. So I don’t want Amazon to go on with their project.”

Regarding jobs, consultation and who stands to benefit, Chief Sandra says indigenous people, who have historically been marginalised through sub-par education, if any, would not be considered for a job because they have no educational background.

She adds that only the government and rich people will benefit, not locals. “No one that I know was consulted. We weren’t aware.”

!Gari !Ous of !Khora||gau||aes Cultural Council, says the site is significant to him because “many of my legendary forefathers spilled their blood on this site”. What pains !Gari !Ous most that there is no memorial, nothing that honours those who lost their lives there.

Dulcie, an indigenous elder who grew up on the Cape Flats, shares memories of growing up and says her people have always had profound respect for “The Rivers”. She says, “Our parents would recollect the stories of our forefathers, who had been buried in the area after they had died at the hands of intruders.” Dulcie says the area is sacred and “growing up, it was an honour for us to walk by the river and through the reeds”.

For me, whether you know me as Nadine or Gogo Mmathapelo, this site is sacred and important because it reminds us of how you cannot separate the environment from indigenous people. When we speak of the environment, we are talking about the indigenous people, these things cannot be separated.

How can we allow the descendants of the people who have benefited from our genocide to continue to make decisions for us and decide what is or isn’t our heritage?

How does one decide someone else’s heritage?

The spiritual significance of water and ceremony shouldn’t be discounted either; even today – we still phahla, and perform our traditional cleansings, ceremonies, offerings and many other elements of who we are in sacred terrains such as places where rivers are found. The truth is there is significance and power in how we understand that connecting to the same soil, water, fauna and flora after everything that has happened still connects us to who we are and those who have departed this realm.

B’ia Bradley shares that, whenever someone visits this country, he welcomes them home, no matter where they are from, because “this is the birthplace of humanity”.

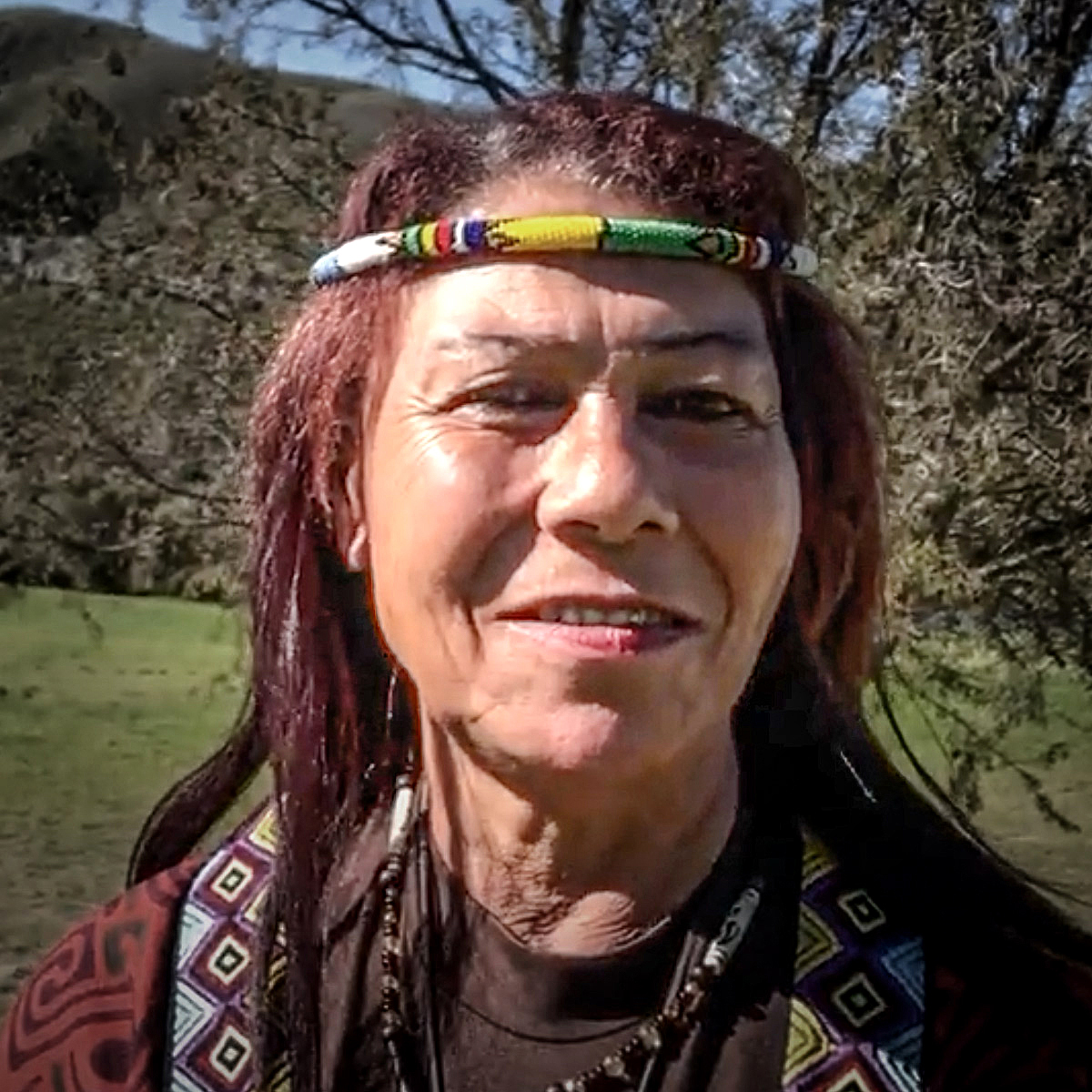

Chief Krotoa echoes these statements and says, “This is the birthplace of the San, the birthplace of the nation, and the birthplace of humanity.”

She proclaims the unity we are experiencing in all walks of life is not by chance. She says it has “taken everyone and put them on the back foot because they never expected it after so many decades of separation”. It can only be described as a miracle of unity.

Chief Autshumao reminds us colonisation was about land and, in turn, it caused dispossession which we are still experiencing and fighting – as in the case of the redevelopment of the River Club.

Gorogloeg, an aboriginal activist, reminds us that the River Club area is sacred to all because it is a very historical site, “Not just in //Hui !Gaeb alone, but the whole of southern Africa.”

Khoebaha Arendse comments that, for him, it is not just about imposing on indigenous people but also that it is an imposition on a piece of land that “carries with it millennia of history in terms of the creation … it speaks to the only place of liberty and resistance that we can relate to”.

How can a place that represents a people, resistance and heritage not be considered a place of great significance?

Chief Eben Basson describes himself as a doctor who uses traditional methods to heal. These methods include herbs and plants. Chief Eben says growing up under apartheid meant there weren’t opportunities to visit a doctor for someone who was unwell and far from town. This is a major motivation for Chief Eben to oppose the redevelopment of the River Club and other sites worldwide that negatively affect the environment.

Chief Eben teaches that, “We are nothing without the land, soil, water and herbs.” We can’t afford to lose our indigenous practices and ways of healing. By destroying our sacred spaces we are destroying the herbs that have healed our forefathers and us.

Paramount Chief Hennie Fortuin of the Cochoqua in the Boland Cape Winelands echoes all these sentiments. The development is unacceptable and “we decided we are not going to authorise it, and it is ours as the first nation’s decision and that decision is final. There is nothing left to negotiate about it because negotiations were not discussed with us the previous time, so we cannot approve it.”

Chief Fortuin pleads with the South African people to be sensitive towards this issue and its importance. He says, “This development will take away our heritage and erase all the importance of what has happened there, including the memory of our ancestors.”

Dr Yvette Abrahams of the San and Khoi Centre at the University of Cape Town said she could sum up why she is against the redevelopment of the River Club in less than a minute. It’s simple: “Because we said no.”

In truth, that is the crux of the issue: developers attempt to build on a sacred site of indigenous people, the indigenous people oppose, and therefore it is as simple as “no”.

Indigenous people were not consulted about redevelopment of a space that is sacred and of great importance. Those are the voices that should have been consulted first and considered, those are the people who should have been met to consult in the way they perform consultations according to customs, and those are the people who should have been heard the first time they said “no”.

How can someone else decide what is sacred to a particular people and what is not? You simply cannot decide and attempt to bargain your way into gaining control of indigenous land as if we are still in the 1600s.

The painful reality is we are still removed from our own land, spaces and resources and our right to have a say is ignored. Something has to shift and that shift can only happen when we are given back our agency to speak up and be a part of decisions.

At the end of the day, what benefits are there to freedom and post-apartheid and apparent reconciliation without inclusion, equity and justice. DM/MC

Nadine Dirks is a writer and activist. Her work in intersectional feminism, gender, sexuality, communications and reproductive health can be found in publications worldwide. She is campaign manager of the Liesbeek Action Campaign.

Source

Language of the news reported

Copyright © Source (mentioned above). All rights reserved. The Land Portal distributes materials without the copyright owner’s permission based on the “fair use” doctrine of copyright, meaning that we post news articles for non-commercial, informative purposes. If you are the owner of the article or report and would like it to be removed, please contact us at hello@landportal.info and we will remove the posting immediately.

Various news items related to land governance are posted on the Land Portal every day by the Land Portal users, from various sources, such as news organizations and other institutions and individuals, representing a diversity of positions on every topic. The copyright lies with the source of the article; the Land Portal Foundation does not have the legal right to edit or correct the article, nor does the Foundation endorse its content. To make corrections or ask for permission to republish or other authorized use of this material, please contact the copyright holder.