Location

The International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) was established in 1977. It is one of 15 such centers supported by the CGIAR. ICARDA’s founding mandate to promote agricultural development in the dry areas of developing countries remains highly relevant today.

ICARDA works with a tight focus on the problem-solving needs of resource-poor farmers, achieving this through the in-field delivery of its research outputs. Although global food production has increased by 20 per cent in the past decade, food insecurity and poverty remain widespread, while the natural resource base continues to decline.

International research centers such as ICARDA, which have helped drive previous improvements, continue to deliver new technologies to support sustainable growth in agriculture, and crucially, to work with a wide range of partners to accelerate the dissemination of these technologies.

ICARDA’s biggest strength is its staff – 600 highly skilled men and women from 32 countries. Our research and training activities cover crop improvement, water and land management, integrated crop-livestock-rangeland management, and climate change adaptation.

Other interventions include:

- Water harvesting - supplemental irrigation and water-saving irrigation techniques

- Conservation agriculture methods to reduce production costs and improve sustainability

- Diversification of production systems to high-value crops – horticulture, herbal and medicinal plants

- Integrated crop/rangeland/livestock production systems including non-traditional sources of livestock feed

- Empowerment of rural women – support and training for value-added products.

The ICARDA genebank holds over 135,000 accessions from over 110 countries: traditional varieties, improved germplasm, and a unique set of wild crop relatives. These include wheat, barley, oats and other cereals; food legumes such as faba bean, chickpea, lentil and field pea; forage crops, rangeland plants, and wild relatives of each of these species.

ICARDA’s research portfolio is part of a long-term strategic plan covering 2007 to 2016, focused on improving productivity, incomes and livelihoods among resource-poor households.

The strategy combines continuity with change – addressing current problems while expanding the focus to emerging challenges such as climate change and desertification.

We work closely with national agricultural research systems and government ministries. Over the years the Center has built a network of strong partnerships with national, regional and international institutions, universities, non-governmental organizations and ministries in the developing world and in industrialized countries with advanced research institutes.

THE ‘DRY AREAS’

Research and training activities cover the non-tropical dry areas globally, using West Asia, North Africa, Central Asia and the Caucasus as research platforms to develop, test, and scale-out new innovations and policy options.

Dry areas cover 41 per cent of the world’s land area and are home to one-third of the global population. About 16 per cent of this population lives in chronic poverty, particularly in marginal rainfed areas. The dry areas are challenged by rapid population growth, frequent droughts, high climatic variability, land degradation and desertification, and widespread poverty. The complex of relationships between these challenges has created a "Poverty Trap."

Members:

Resources

Displaying 156 - 160 of 431Publication Review: Multifaceted Impacts of Sustainable Land Management in Drylands

Water management practices such as water harvesting yield important environment and socio-economic benefits by reducing environmental risks, improving soil

health and increasing crop yields, particularly in dry areas. Several types of water harvesting practices can be implemented depending on soil type, geology, material

and labour force availability: floodwater harvesting practices, micro and macro catchment water harvesting, and roof-top or courtyard rainwater harvesting. These are

Publication Review: Lessons learned in sustainable land management in drylands

Extreme weather conditions such as drought and floods, a changing and more variable climate, and the unsustainable use of the natural resources are amongst

complex factors that drive land degradation. This in turn negatively affects land productivity, food security, socio-economic stability, health and wellbeing, and the

provision of other ecosystem goods and services for billions of people worldwide. In drylands, these negative effects are felt ever more strongly given the already

limited natural resources that characterize these regions.

Gap in science and practice of land restoration

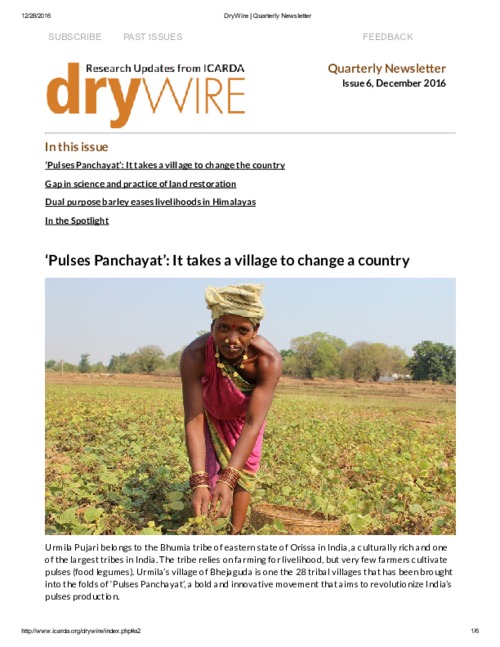

Urmila Pujari belongs to the Bhumia tribe of eastern state of Orissa in India, a culturally rich and one

of the largest tribes in India. The tribe relies on farming for livelihood, but very few farmers cultivate

pulses (food legumes). Urmila’s village of Bhejaguda is one the 28 tribal villages that has been brought

into the folds of ‘Pulses Panchayat’, a bold and innovative movement that aims to revolutionize India’s

pulses production.

Congruence of appropriation and provision in collective water provision in Central Namibia

Achieving cooperation in natural resource management is always

a challenge when incentives exist for an individual to maximise her short term

benefits at the cost of a group. We study a public good social dilemma in water

infrastructure provision on land reform farms in Namibia. In the context of the

Namibian land reform, arbitrarily mixed groups of livestock farmers have to share

the operation and maintenance of water infrastructure. Typically, water is mainly

used for livestock production, and livestock numbers are subject to high fluctuations

Sustainable intensification of agriculture for human prosperity and global sustainability

There is an ongoing debate on what constitutes sustainable intensification of agriculture (SIA). In this paper, we propose that a paradigm for sustainable intensification can be defined and translated into an operational framework for agricultural development. We argue that this paradigm must now be defined—at all scales—in the context of rapidly rising global environmental changes in the Anthropocene, while focusing on eradicating poverty and hunger and contributing to human wellbeing.