Building solutions for long-term sustainable livelihoods in urban contexts

From 6-18 November, Egypt will host the COP27 Climate Summit. This year marks the 30th anniversary of the adoption of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. Despite this long trajectory and the progress made, climate change has increasingly severe effects across the world. The LAND-at-scale program acknowledges the central role of climate change. In a short series of blogs, the knowledge management team highlights the diverse impact that climate change has on communities across the world, and how LAND-at-scale projects contribute to adaptation and mitigation measures on the ground. In this blog we talk to Karel Boers, who works with IOM UN-Migration as a durable solutions program M&E coordinator for the Saameynta program in Somalia.

The Saameynta project promotes the sustainable integration of displaced communities in urban areas. How does climate change play a role in this project? Do you have insights into how many of the IDPs that move to the cities do so because of climate related developments?

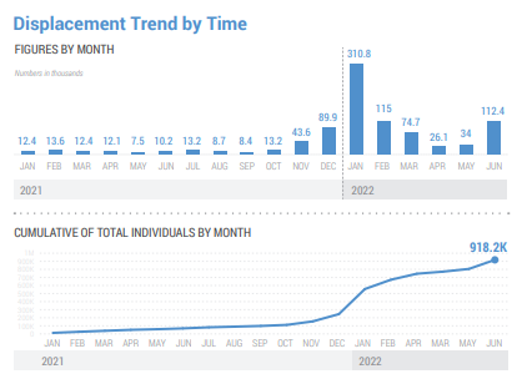

Climate change plays a massive role in this project. The current drought, the worst the country has experienced in the last 40 years, is the major driver of displacement in Somalia. Over one million Somali’s have been displaced since January 2022[1]. According to a new study which carried out research on rural mobility, displacement, food security and livelihoods in five regions the key drivers of displacement can be broadly categorized as either climatic-induced or human induced[2], with an overwhelming majority (90.5%) of respondents indicating drought as the biggest driver of displacement that has forced households to displace into urban areas. The study noted the main push factors to be drought, flood, food insecurity, human insecurity, lack of income, lack of pasture/livestock feed due to drought conditions, as well as conflict. Notably, concerning conflict, 79.3% of the conflict measured was in fact over natural resources, such as land, water and/or pasture.

Figure 1: Number of people displaced by drought

Source: Drought Displacement Monitoring Dashboard (June 2022) (reliefweb.int/report/somalia/drought-displacement-monitoring-dashboard-june-2022)

How does the Saameynta project, and the LAND-at-scale component in particular, address the immediate consequences of climate change?

During 2022-2025, the Saameynta project plans to integrate 75,000 internally displaced people (IDPs) in Baidoa, Bossaso and Beletweyne. Baidoa where the program focuses during 2022-2023, is one of the worst drought- affected areas in Somalia.[3] Saameynta project partners (IOM, UN Habitat and UNDP) address both the immediate and medium-long term consequences of this drought-driven migration through an integrated humanitarian development peace nexus approach. Saameynta works with the Government of Somalia, local communites, and the private sector to make the agricultural-based economy and communities in Baidoa stronger. The Baidoa economy relies on natural resources that are affected by man-made degradation, making the city more vulnerable to poverty and food insecurity. In supporting private sector growth, it is expected that by the end of 2022, 100 small firms will have access to business development services and finance. This support will also trigger green livelihoods at local level. Other activities from Saameynta aimed at long-term integration of IDPs in the urban context will support public services for agricultural growth such as veterinary services and pest control. These are public services under the responsibility of the Ministry of Agriculture in South West State.

By applying a long-term vision, Saameynta prepares IDPs to build sustainable livelihoods in the cities. This prepares them to survive not just this drought, but also future natural disasters, which climate change is making more frequent and severe.

The pressure on urban centres in Somalia is enormous. Saameynta is particularly looking at the long-term integration of IDPs in urban settings. Considering the aspect of climate change, can you tell us what can enable people to firstly remain in rural areas, and secondly, to return to these areas so as to reduce the pressure on Somali cities?

As mentioned, the main push factors for displacement are climate or environment related. Approximately 60% of the Somali population practice pastoralism, with another 15% practicing agriculture. An enormous part of the population is directly reliant on the climate/environment for their livelihoods but have little coping alternatives when climate shocks such as drought or flood occur. For people to remain in rural areas of origin, the threat of climatic shocks needs to lessen or disappear. Considering that future projections predict a temperature increase between 1.4 and 3.4 degrees Celsius, sea level rise and more frequent periods of flooding and drought[4], this is not a realistic scenario. What is therefore imperative is building communities’ long-term resilience to climatic shocks, also in urban contexts, as well as the restoration and preservation of the environment, ecosystems and natural resources through nature-based solutions which are central to the livelihoods of the majority of people.

The earlier mentioned study identifies key factors including the provision of basic service infrastructure in secondary and tertiary cities; creation of livelihood opportunities through economic investment programs for both urban and rural communities; ensuring displacement affected communities are supported with livelihood skills training supported with financing for SME start-ups. Several entry points to these activities are supported and being implemented through the Saameynta project with the objective to create the conditions for (re)integration in the urban economy and alleviate the pressure on services and local economy.

Many of the IDPs you work with and for have lost their livelihoods, and their homes. How do you envisage the topic of Loss and Damage to address these losses?

Losses and damages[5] can be addressed though community-based resilience approaches and programs aimed at strengthening the adaptive capacities of communities. These include livelihood diversification; scaling up social safety net programs; investments in renewable/clean energy technologies; scaling up resilient urban infrastructure projects; and effectively costing and timely conducting of loss and damage assessments for effective community recovery. In this regard, Saameynta specifically develops resilience approaches through community-identified priorities such as the construction of water infrastructure, rehabilitation of drainage systems, operationalization of environmental related policies, addressing shelter/housing policy gaps using environmentally-friendly housing typologies, and the establishment of solar powered micro-irrigation schemes.

What is the main outcome you want to see from the upcoming COP27 and why?

Somalia has contributed less than 0.003% of global greenhouse gas emissions, yet it is at the forefront of climate change and climatic shocks. Currently, over 8 million people (over half) of the population are in need of humanitarian assistance. On average, between 1990 and 2019, 64 people per 1000 have been affected by climate impacts in Somalia. This is stark when compared to the USA for example, the second highest global emitter, where we see 12 people affected per 1000. Indeed, at a local level individuals can engage in maladaptive practices which degrade the environment, such as cutting down trees or overgrazing, but the main driver of major climate shocks does not lie with the communities who are experiencing them first-hand. Wealthier nations are more able to pay for, and recover from, climate impacts than developing countries. Fragile states also have difficulty accessing climate financing, even though they are experiencing the worst of the impacts. Countries like Somalia, who have contributed the least to climate change but whose population is experiencing extreme suffering from the impacts of climate change need adequate financing to cope with and recover from these impacts.

By that, we want COP27 to mobilize reliable long-term financing to build resilience and adapt to the inevitable impacts of climate change, to deliver on the commitments to finance climate action made on former COPs as this may be one of the last calls to make change happen before the damages caused by climate change on people and planet are irreversible.

[2] FAO (January 2022): Rural Mobility, Displacement, Food Security and Livelihoods in Somalia Report